From Conflict to Collaboration: Dan Dagget’s Journey Toward Conservation Through Ranching

Images courtesy of Dan Dagget.

When Dan and his wife, Trish, moved to Flagstaff in 1980, they carried with them a deep commitment to environmental activism. In Ohio, they had lived on a small farm and organized their community to stop a neighboring coal company from surface mining the land. That experience had cemented their belief in the need to protect open, natural landscapes from exploitation.

Once in Arizona, they hosted meetings at their home to discuss threats they saw on the horizon. “We began having meetings about how ranching was a threat to land that was valuable as wild, open habitat and thus needed to be protected,” Dan recalls. “I even received an “Environmental Hero” award from the Sierra Club for my work to limit predator control programs, among other things.”

Yet what began as an effort to challenge ranching slowly grew into a journey that reshaped Dan’s entire view of how land could be managed in order to sustain its natural health. Ranchers invited Dan to visit their operations and see firsthand what they were doing. At first skeptical, Dan accepted an invitation to compare two neighboring ranches.

One was managed by an environmental group that had removed grazing entirely. Next door, a rancher was applying a new method called holistic management, pioneered by Allan Savory who observed how wildebeest lived in synergistic harmony with wild grasslands in Africa. The difference was startling.

“On the protected ranch, grass was sparse and shorter than our shoes,” Dan says. “Next door, on the holistically managed ranch, grass was dense and waist high.”

Holistically managed ranch in southern Arizona (left) compared to ungrazed “protected” ranch across the fence line (right). These pictures were taken on the same day.

Lessons from the Land

What Dan discovered was that ranching, when done in a way that mimicked natural herd patterns, could in fact achieve many of the goals environmentalists had long sought: healthier grasslands, greater biodiversity, and more resilient ecosystems.

Through his research for Beyond the Rangeland Conflict and Gardeners of Eden, he encountered examples across the Southwest where carefully managed cattle were not degrading the land but restoring it.

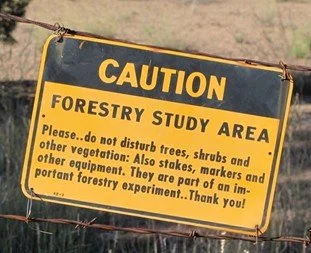

One vivid example came from a U.S. Forest Service exclosure near Drake, Arizona. Grazing had been excluded since 1946, and monitoring lines had been established to track vegetation. By the 1980s, the exclosure was so barren that researchers had largely stopped counting plants because there was so few to count. Outside the fence, however, where ranchers continued to graze cattle with conservation in mind, grasses were so dense they were difficult to tally.

Images, including the soil temperature reading, from the Forest Study Area exclosure near Prescott, AZ where grazing was prohibited (top row). Images from adjacent grazed land (below) were taken on the same day in 2014.

Perhaps the most surprising case came not from rangeland but from a pile of copper mine waste near Globe, Arizona. For a century, attempts at restoration had failed. Rancher and former Mayor Terry Wheeler tried a different approach: convincing the mining company to turn cattle onto the mine tailings and keep them moving in herds. The animals stomped uneaten hay and seed into the soil, fertilized it, and broke the crust. Against all odds, vegetation took hold and the site came alive.

“These are the kinds of results that stick with you,” Dan says. “They make you rethink the relationship between grazers and grasslands.”

Photos of the copper mine waste piles near Globe, AZ prior to (left), during (middle), and after restoration (right) through grazing.

Rethinking the Relationship

Over time, Dan came to see that cows, far from being outsiders to the ecological system, can play a role much like wild grazers once did. His view aligns with James Lovelock’s “Gaia” hypothesis, which describes Earth as “a living system whose living participants (plants and animals) work together to sustain the ecosystem’s livability”.

“Just as grasses feed grazers, grazers benefit grasses,” Dan explains. “They trim plants so they can regrow effectively. They fertilize. They break soil crust so water can infiltrate instead of run off. They prevent dried grasses from becoming fuel for fire. And they encourage root growth that sequesters carbon.”

The soil implications are profound. On one fall day at the Drake exclosure, Dan measured the surface temperature of ungrazed land at 122°. Nearby grazed land measured just 78°. On an ungrazed site near Sedona in July, the soil temperature hit 171°. “If that land had been grazed, it likely would have been 60 degrees cooler,” Dan says. “That’s not just a benefit for plants—it’s a direct impact on climate.”

Building Something New: Diablo Trust

Dan’s evolving perspective led him into collaboration with ranchers in northern Arizona. In the early 1990s, he joined with families from the Bar T Bar and Flying M ranches, along with conservationists, agencies, and researchers, to form the Diablo Trust.

“What makes Diablo Trust unique is the people,” he reflects. “They’re willing to work, keep working, and bring more people together. That’s what it takes today.”

For Dan, Diablo Trust represents not just a strategy for land management but a hopeful model for society. “In the way politics and society are going today, examples of working together are more important than ever. That’s what Diablo Trust provides.”

Challenges and Opportunities Ahead

Looking ahead, Dan sees both daunting challenges and exciting opportunities for ranching as a conservation tool. Climate change, wildfire, and ongoing misconceptions about grazing remain obstacles. But there is also growing recognition, even among mainstream environmental organizations, that ranching can be part of the solution.

Groups like the National Audubon Society, The Nature Conservancy, and World Wildlife Fund have begun to collaborate with ranchers on grazing strategies that benefit birds, wildlife, and grasslands. “We need to build on those successes,” Dan says. “And we need to reward the people on the ground who are proving these ideas work.”

Most of all, he argues, we need more visible, well-documented examples that demonstrate what effective grazing can accomplish and a commitment to telling those stories widely.

A Call to the Next Generation

For younger ranchers, conservationists, and students, Dan offers clear advice: “Get involved. Exercise your creativity. Do more research. Join more work-together groups. Measure success in terms of real eco-results achieved instead of in terms of victories won over someone you’ve identified as an opponent.”

From an environmentalist who once opposed ranching to a collaborator working alongside ranchers, Dan Dagget’s journey shows how staying curious, listening, and looking at the land with fresh eyes can open up new possibilities.

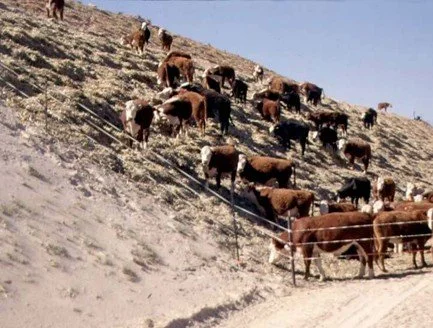

Images of partners over the years coming together to learn from the land.